Peter the Great… of Grande Prairie

Through political and military action Peter the Great of nineteenth century Russia propelled a backward European nation onto the world stage as an economic and military power to be reckoned with. Some may think that comparing Grande Prairie’s Pete Wright to the re-known Russian Emperor is excessive. However, Pete Wright’s hockey exploits played an important role in bringing attention to Grande Prairie everywhere he played the game; throughout Canada, the US, Europe and the world. Everywhere Pete played he turned heads. On the world stage he was a defensive stalwart on the Edmonton Mercurys, a team that won the 1950 World Ice Hockey Championships in London England and many more remarkable achievements followed.Pete was the first Grande Prairie lad to break into the pros. How that was accomplished is remarkable considering Grande Prairie had no organized hockey program, no outside hockey connections and no record of hockey scouts snooping around the town when Pete was a kid. We can only speculate that he heard about try-outs for the Edmonton Athletic Club (EACs) who played in the Edmonton Junior Hockey League. Like young Grande Prairie hockey hopefuls after him it is likely he packed a duffel bag with his hockey equipment and a few clothes and hitch hiked to the big city. Local fans having seen Pete play with Grande Prairie’s senior D- Company at age seventeen knew that he would make the cut.

During Pete’s youth Grande Prairie was still a frontier town in many ways and its economic potential still unrealized. However, Grande Prairie and district was rich in natural resources. As early as 1879, in a geological survey by George Dawson he reported “the soil of Grande Prairie is almost everywhere exceedingly fertile, and is often for miles together of deep rich loam which it would be impossible to surpass in excellence.” (The Grande Prairie of the Great Northland, 2005, p. 7). Reports of that nature stimulated a land rush to the Peace River country. While the major rush for land was over, homesteads were still available when Pete was born in 1927. “My Dad filed for a homestead five miles south of town in 1928.” (Ron Neufeld). Along with available land an abundance of timber was readily available, coal was mined and the discovery of other natural resources followed. The construction of the Alaska Highway in 1942 when Pete was fifteen did much to focus attention on the North. In recent years the discovery and extraction of oil deposits has brought financial notoriety to Grande Prairie and today it is one of Alberta’s richest cities. As for resources in the realm of sports, when Pete was a teenager (1940 – 46), Grande Prairie’s talent in sports was relatively unknown and untapped.

Wealth in natural resources fails to address the character of a town and its people. In keeping with it’s largely rural and frontier nature, townspeople in Pete’s era were generally open, friendly, helpful and honest. It seems a paradox that in spite of a rugged individualism born of an environment that had a harsh side neighbors looked out for one another. A further important factor in Pete’s development was the effect of the Great Depression and the uncertain financial circumstances in which Pete grew up. Pete’s “hard work ethic” was at least in part a product of the depression. Pete made the best of these external forces. He was friendly, open and helpful – what you saw was what you got - tough but sensitive, stubbornly determined and hard working.

Of course Pete was also shaped by family circumstances. He was the youngest of five boys – all of them fine athletes excelling in both hockey and baseball. Pete was too young to serve his country in WW11 but his older brothers, four of them, joined the war effort. In December, 1943 four Grande Prairie boys were killed in active duty overseas. Among them was Kelly Wright, Pete’s older brother. Lieut. M. R. “Kelly” Wright was educated in the Grande Prairie school system, received his “wings” at Claresholm in 1942, and was decorated with the Distinguished Flying Cross following his death. He was a fine all around athlete and like Pete an outstanding hockey player.

GP Hockey Legend Ken Head was Pete’s contemporary. He reports that Pete was an even better baseball than hockey player and that he preferred baseball (personal interview with Stan Neufeld, June 25, 2013). Pete’s hockey records and statistics are available for all to see but we can thank Ken for sharing information about his prowess in baseball and personal characteristics that reveal the measure of the man. Ken and former Mayor and GP Hockey Legend Oscar Blais played baseball with Pete. After a home game they taped what they thought was a particularly long hit by Pete. It measured 503 feet. In an interview with Stan Neufeld, Ken recounted some stories that illustrate Pete’s sense of humour and his competitive nature. Pete was the catcher on Grande Prairie’s baseball team. One of the team’s pitchers, Rudy Cepella was a “junk ball” pitcher, not known for generating much heat. Pete, felt that Rudy could do better and during a game made this point by throwing his mitt into the dugout. When Rudy protested Pete implied that he could “barehand” his pitches – the mitt was unnecessary equipment. On another occasion Pete told a base runner on his team that he could run faster wearing hip waders. To prove his point Pete came to the next game wearing hip waders and in a race around the bases he crossed home plate as his teammate rounded third. Ken believes that if Major League scouts had discovered Grande Prairie in Pete’s era he would have been a pro baseball player.

In spite of Pete’s ability and interest in baseball it was as a hockey player that he would make his mark and bring attention to his hometown. He learned to skate and played his first hockey on Bear Creek. Bear Lake is approximately 16 miles from Grande Prairie as the crow flies and is connected by the meandering, muddy waters of Bear Creek. Pete, Ken Head and their buddies often played shinney on the creek and Pete jokingly once told Ken “My favourite place to play hockey is in the Bear Creek covered arena – under the railroad trestle that crossed the creek. He went on – one day during a match I got a break away and was caught the next day on Bear Lake.” Little did anyone know when he was a kid that Pete would play in many of the finest, best known arenas in the world and make his presence known.

As noted earlier, Pete’s first hockey away from home was with Edmonton’s junior EACs. During the course of his professional hockey career he played in five leagues and eight different teams. Leagues included the American Hockey League, the British National League, the Eastern Hockey League the Quebec Senior Hockey League and the Western Hockey League. The Buffalo Bisons, Earl’s Court Rangers, Edmonton Flyers, New Haven Blades, New Westminster Royals, Seattle Americans, Sherbrooke Saints and Victoria Cougars were pro teams for whom he played. The details of his story are a bit fuzzy between 1947 after Pete played for the EACs and two years later when he showed up in a Waterloo Mercury uniform to represent Canada in the World Hockey Championship tournament. It is likely that Pete was invited to a Montreal Canadians training camp at the beginning of the 1947 season and it is widely believed that he was earmarked by the Habs to replace Butch Bouchard on the blue line. (Herald Tribune staff Todd Maxwell). Sadly Pete broke his pelvis, an injury that would have ended a career in hockey for most players. Not so for Pete. In his words “ the incident set me back a bit.” Two years later he re-appeared on a hockey roster to represent Canada on the world stage playing a rearguard position with the Edmonton Mercurys, a team of amateurs that many feared would be an embarrassment to their country. Not so – prior to the World Championship series the team traveled across Europe playing thirty-three exhibition games in 3 ? months. They won all but three games that were lost to professional teams. The World championship was a ten-day round robin event that saw the Mercurys win all of their eight games. During the series they scored 88 goals – only five goals were scored against them. A victory parade of 60,0000 fans lined the streets of Edmonton to welcome the Mercurys home. Pete’s performance in the series re-ignited his hockey career.

The following year Pete returned to England to play for the Earl’s Court Rangers of the British National League. This marked the beginning of his adventures as a professional. It was reported that during his first game the hometown fans booed him following a hard but clean hit that sent an opponent spinning into the boards. The coach took him aside and told him that after knocking down an opponent he should help the player to his feet. Pete complied and became a crowd favorite. He was an All Star in the English League. In the first of his two-year stint in the American Hockey League with the Buffalo Bisons (1953 – 1955) Pete was Rookie of the Year and the Bisons won the AHL championship.

In every league and with every team he played Pete established himself as the hardest hitter and toughest performer. Although Pete did not look for fights he was inordinately strong and a formidable scrapper. “Pete was neither rowdy nor ill tempered but no-one pushed him around.” (Sports Reporter Orm Schultz). He was fearless and fearsome. NHL Hall of Fame Kenny Reardon, a tough and rugged blue-liner with the Canadiens, told Ken Head “Pete Wright was the toughest guy he ever saw on a pair of skates”. In the same vein it is reported that Don Cherry stated in Hockey Night In Canada, “Pete Wright from Grande Prairie was the toughest player I ever played against.”

More importantly were Pete’s skill as a “stay at home” defenseman. “Pete’s approach to the game was to look after your own end of the rink and the offence will look after itself.” (Stan Neufeld). “Nobody, reported Ken Head, could beat him outside and if you tried to cut back into the center of the ice that’s when he would hit you and he was unbelievably solid on his skates.” In terms of offence Pete was noted for his passing skills. “He had remarkable control of the puck in his own end, get you breaking into their zone and put the puck right on your stick.” (Ken Head).

Pete never lost sight of his roots and in 1960 he returned to Grande Prairie, opened a sporting goods store, was President of the Athletic Association, coached several levels of hockey and baseball, for a number of years was playing coach of the senior Athletics and later played the game as an old timer. While Pete continued to enjoy the game as a player he was more interested in contributing to the development of young people. He immediately became a hero and role model in town. His store was a gathering place for kids. If profit margin is the yardstick for success in business Pete was not a particularly good businessman. He was more interested in ensuring that kids who wanted to play the game were able to do so and if that meant giving them a “deal” for needed equipment Pete made sure that it was available to them. As interested as he was in helping them become better hockey players Pete was insistent that they should complete their education – school first – hockey second.

Pete did not forget that when he was a kid hoping to make a career of the game there were no connections from Grande Prairie to hockey elsewhere. Because of his reputation and connections he scouted local talent for junior hockey in Edmonton and beyond. “I was one of Pete’s projects, said Stan Neufeld, and although I did not move on to make a career of hockey it was Pete that provided that opportunity for me. After trying out for the Oil Kings I returned to Grande Prairie as a sports writer and one of the perks was writing about my hockey hero – Pete Wright. Even better – I had the pleasure of playing with him when he was playing coach of the Athletics. Every young hockey player in town dreamed of playing with Pete.” (Stan Neufeld). Stan went on to say “Pete was not over protective of the young players on his team but he would not tolerate any opponent taking unfair liberties with his teammates. I did not have Pete’s size or strength, reported Stan, but nonetheless I tried to emulate him on the ice sometimes engaging in tilts with opponents older, bigger and tougher. After one such occasion I returned to the bench and Pete announced he was going to advertise his sporting goods store on the bottom of my skates. On another occasion I got cut up in a scuffle and needed stitches whereupon Pete produced his first aid kit that included a needle and thread for on the spot repairs. One of my proudest hockey moments was when I was given Pete’s number five sweater to wear.” (Stan Neufeld).

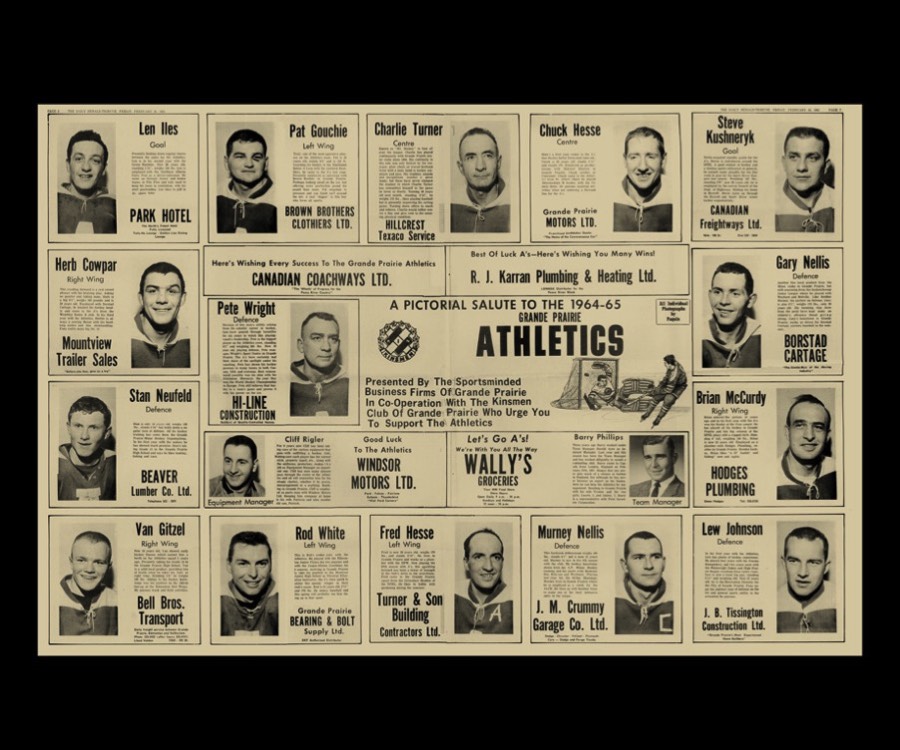

Photo: Daily Herald Tribune

Pete and GP Hockey Legend Max Henning were best of friends played hockey together and were hunting partners. According to Max, Pete carried a supply of horse liniment that he alleged was a cure for all manner of aches and pains. “If it was good enough for horses, noted Pete, it was good enough for me.” (Max Henning). One wonders what kind of success Pete had as a hunter. The odour of horse liniment would surely have repelled wild game anywhere in his vicinity. Max’s son, Cam was one of Pete’s outstanding protégés. “ I was lucky, said Cam, I received special attention from Pete and he taught me the art of hitting. For example he instructed me to look at an opponents chest – always play the man, not the puck.” Cam confirmed Ken Head’s claim that Pete was a master at controlling the puck in his own zone. Cam recalls “Pete once received a penalty for delay of game when a referee decreed that Pete ragged the puck too long behind the net while killing off a penalty. No one could strip him of the puck.”

David Emerson was another budding hockey talent who admired and was influenced by Pete. “As a hockey coach for the Athletics Pete was a respected no nonsense pillar of the team. His patented slap shot had a short 18 inch acceleration arch that drilled the puck six inches off the ice making it ideal for deflection or just beating the goalie in those difficult to cover lower corners. And nobody messed with Pete whose physical strength made him a crushing body checker and fighter. For a couple of sixteen year old rookies in a very tough league having Pete Wright watching your back was a life saver that allowed young players to survive and develop. Remember - the South Peace League in those days was a so-called “outlaw league” that attracted some rough characters banned in other Canadian leagues by the CAHA.”

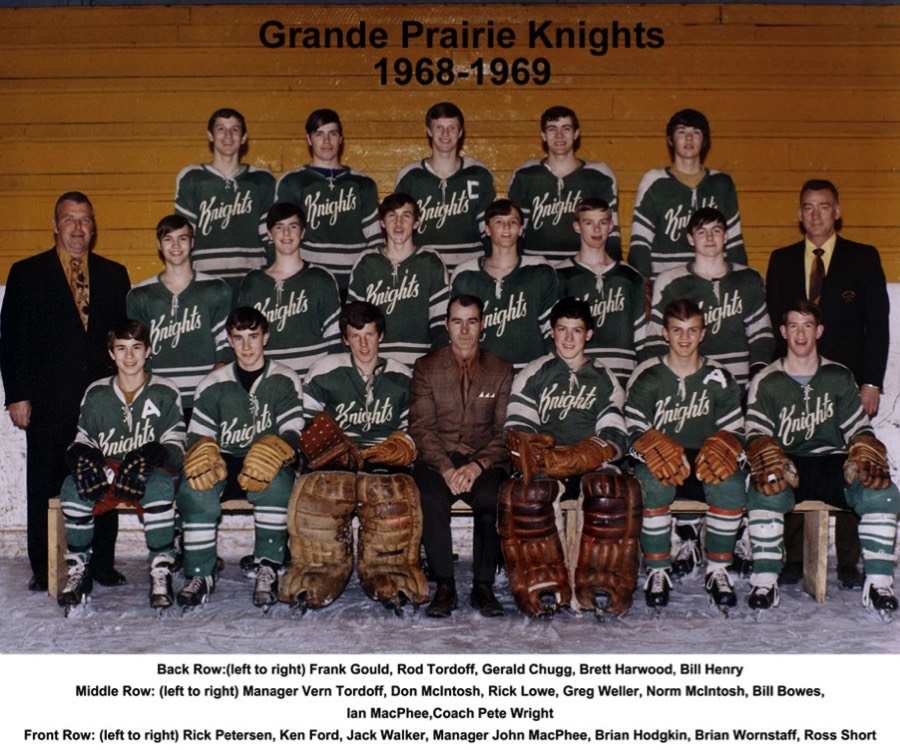

Pete’s priority and most enduring contribution was coaching younger players. He believed that although senior hockey was a revenue generator “that equal or even greater attention should be given to the younger set.” He emphasized the teaching of fundamentals – skating, shooting and passing. It annoyed him when parents failed to support and show interest in their kids. “Ninety percent of the parents whose kids I coach have never seen them play.” said Pete. (Stan Neufeld). It would be interesting to hear what Pete might have to say today to over-involved and meddling parents. In recognition of his contribution to minor hockey, each year Grande Prairie’s Minor Hockey Association confers an award to the best AAA Midget defenseman in Pete’s honour. Award winners are reminded to respect his memory by setting wonderful examples to teammates and coaches. Below is a picture of Pete with one of the teams he coached.

It was a shock to the community and a huge loss when Pete died suddenly at the age of 62. Pete had spent a total of 48 years in Grande Prairie, interrupted at age 19 to make his mark nationally and internationally as a star in hockey. Fourteen years later at age thirty- three he returned to his hometown and the next twenty-nine years were devoted to entertaining hometown fans with his skillful and rugged playing ability but more importantly to coach and work with local kids. Pete was predeceased by his son Jerry and left behind his wife Elvie, children Donna and David and four grand children. Upon news of his death tributes poured in with reminders of his accomplishments as a hockey player, his character and of the influence he had on young people in Grande Prairie.

“I would say that he was one of the best athletes Grande Prairie ever produced. In his day he was considered one of the toughest guys to play and one of the hardest open ice hitters. He never went looking for trouble but he didn’t shrink from confrontations if they came his way.” (Ken Head). Pete played hockey for Saskatoon Quaker Coach Bill Hunter who stated that in spite of his tough reputation Pete was among the most likeable players he had ever coached. Ken Head concurred that Pete was often the most valuable player on his team and also the most popular. “What kind of man was he-very good man, very fair; none of the guys had any issue with who was in charge. He was very definite, at practices; if you didn’t work he was on your case but treated you fairly but expected lots.” (Barry Edgar). Wright’s brilliant play earned him player awards in five consecutive years. As playing coach he led the athletics to one championship and receive honours as the most valuable defenseman several times.

“The two most influential people as I was growing up in Grande Prairie were Bob Neufeld and Pete Wright. Bob was a mentor and leadership figure while I was in the High School but when school was out it was off to Wright’s Sporting Goods before going to the rink or ballpark. There the conversations were hockey, baseball, fishing and hunting. The sporting goods store was essentially the hang out for those of us old and young that shared these interests and Pete was the role model. He was good humoured, reliable as a friend and incredibly strong both physically and mentally. For many who frequented Pete’s store that was where the stories were entertaining, inspiring and where legends and lore of a small group of fellow sports minded travelers were created.” (David Emerson).

Grande Prairie’s Ian MacPhee has made a career in hockey and was in the front office of the Phoenix Road Runners when he learned of Pete’s death. “Because of Pete I never went to a training camp – NHL or otherwise not knowing what to do. It didn’t matter where I went or who I talked to whether Emile Francis, Keith Alan, John Ferguson or Larry Gordon. They all knew who Pete was. The respect that they had for him was unbelievable. He left his mark long after he played. Everybody would talk to me about Pete when they found out I was from Grande Prairie.” (Ian MacPhee).

Pete put Grande Prairie on the map. He is Peter the Great …… of Grande Prairie.

Grande Prairie Hockey Legends is researched, written and presented by Stan and Ron Neufeld